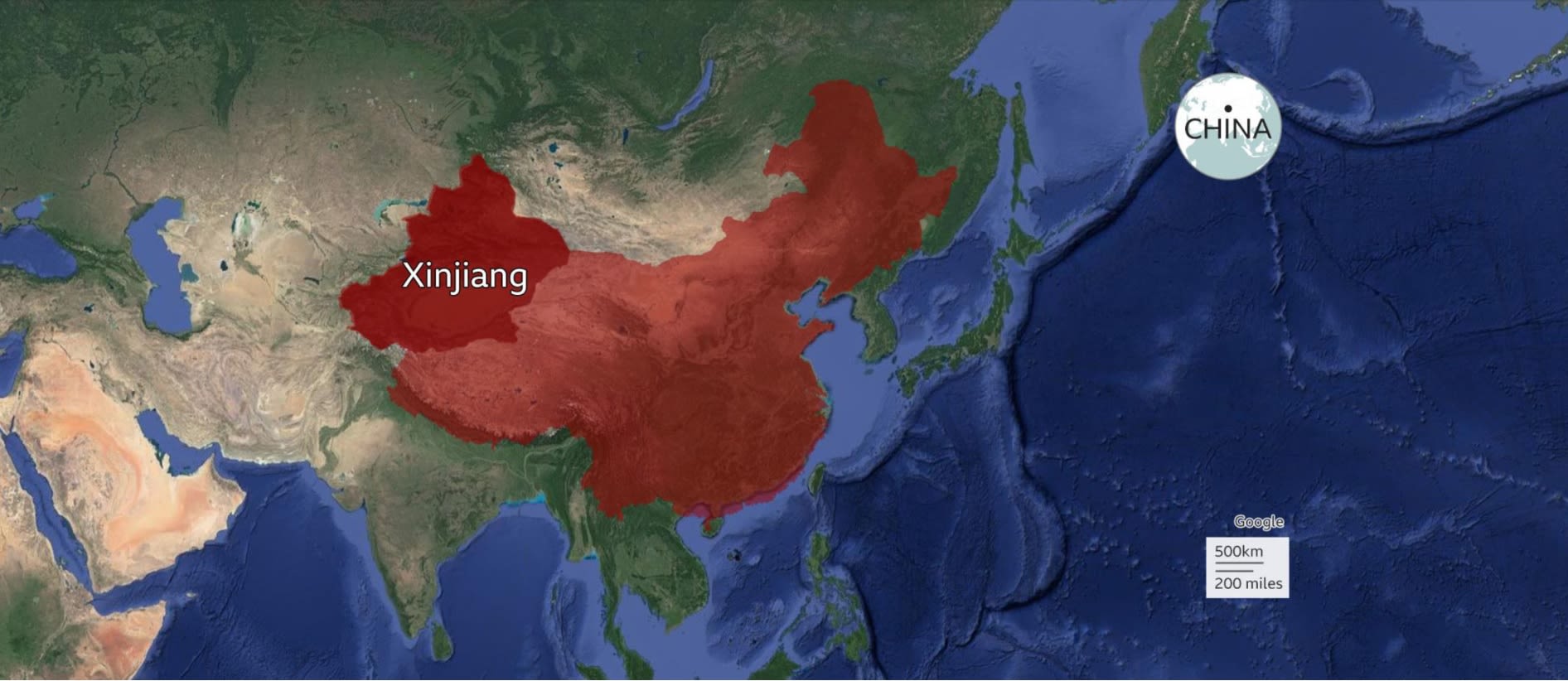

Xinjiang Cotton: More than half a million forced to pick China's tainted cotton

China is forcing hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other minorities into hard, manual labour in the vast cotton fields of its western region of Xinjiang, according to new research.

Based on newly discovered online documents, it provides the first clear picture of the potential scale of forced labour in the picking of a crop that accounts for a fifth of the world’s cotton supply and is used widely throughout the global fashion industry.

Alongside a large network of detention camps, in which more than a million are thought to have been detained, allegations that minority groups are being coerced into working in textile factories have already been well documented.

The Chinese government denies the claims, insisting that the camps are “vocational training schools” and the factories are part of a massive, and voluntary, “poverty alleviation” scheme.

But the new evidence suggests that upwards of half a million minority workers a year are also being marshalled into seasonal cotton picking under conditions that again appear to raise a high risk of coercion.

The documents, a mixture of online government policy papers and state news reports, show that in 2018 the prefectures of Aksu and Hotan sent 210,000 workers “via labour transfer” to pick cotton for a Chinese paramilitary organisation, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.

Others speak of pickers being “mobilised and organised” and transported to fields hundreds of kilometres away.

In 2020, Aksu identified a need for 142,700 workers for its own fields, which was largely met through the principle of “transferring all those who should be transferred.”

References to “guiding” the pickers to “consciously resist illegal religious activities” indicate that the policies are designed predominantly for Xinjiang’s Uighurs and other traditionally Muslim groups.

Government officials first sign “contracts of intent” with the cotton farms, determining the “number of workers hired, the location, the accommodation and wages,” after which pickers are then mobilised to “enthusiastically sign up”.

There are plenty of clues that this enthusiasm is less than whole-hearted. One report describes a village where people were “unwilling to work in agriculture”.

Officials had to visit again to perform “thought education work”. Eventually 20 were sent off, with a plan in place to “export” 60 more.

Camps and Factories

China has long used the mass relocation of its rural poor - with the stated aim of improving their employment prospects - as part of a national anti-poverty campaign.

In recent years, those efforts have gone into overdrive.

Arguably President Xi Jinping’s most important domestic political priority, the goal is to eliminate absolute poverty in time for the Communist Party’s centenary next year.

But in Xinjiang, there is evidence of a far more political purpose and much higher levels of control, as well as massive targets and quotas which officials are under pressure to meet.

A marked shift in China’s approach to the region can be traced back to two brutal attacks on pedestrians and commuters in Beijing in 2013 and the city of Kunming in 2014, blamed by China on Uighur Islamists and separatists.

Its response, from 2016 onwards, has been the building of “re-education” camps for anyone displaying any behaviour viewed as a potential sign of untrustworthiness, such as installing an encrypted messaging app on a phone, viewing religious content, or having a relative living overseas.

While China calls them “schools for de-radicalisation”, its own records suggest that the reality is a draconian system of internment which aims to replace old identities of faith and culture with an enforced loyalty to the Communist Party.

But the construction work didn’t stop with the camps.

Since 2018, a huge industrial expansion has been underway involving the building of hundreds of factories.

The parallel purpose of mass employment and mass internment is made clear by the appearance of many factories within the walls of the camps, or in close proximity to them.

Work, the government appears to believe, will help transform the “outdated ideas” of Xinjiang’s minorities and remake them as modern, secular, wage-earning Chinese citizens.

This facility built in 2017 in the city of Kuqa, has been identified as a re-education camp by researchers

Open-source satellite images show internal security walls and what appears to be a guard tower.

A new factory appeared next door in 2018. Shortly after construction finished, the satellite picked up something significant.

Independent analysts confirm that masses of people, all apparently wearing the same colour uniforms, can be seen walking in close formation between the two sites.

The factory and the camp now appear to have been amalgamated into one large factory complex, plastered with propaganda slogans extolling the benefits of the anti-poverty campaign.

According to local state-run media, the textile factory employs up to 3000 people “under the mobilisation and organisation of the government”.

But it’s impossible to verify who the people in the satellite image are or what the conditions for the workers in the facility are like today.

An August 2016 notice issued by the Xinjiang regional government on the management of cotton pickers instructs officials to “strengthen their ideological education and ethnic unity education”.

And there are many references to how the mobilised cotton pickers are subject to controls and surveillance seemingly at odds with any normal employment practice.

A policy document from Aksu, dated October 2020, decrees that cotton pickers must be transported in groups and accompanied by officials who “eat, live, study and work with them, actively implementing thought education during cotton picking”.

Over the past five years, door-to-door visits have become a key mechanism of control in Xinjiang, with 350,000 officials despatched to gather detailed, intrusive information on every single minority household.

Those being called to work by these “village-based work teams” will be only too aware that they are also instrumental in deciding who should be sent to a camp.

“Completely fabricated”

Xinjiang’s cotton growing industry used to rely on seasonal, migrant workers from other provinces in China.

But cotton picking is notoriously hard work and rising wages and better jobs elsewhere mean the migrants have stopped coming.

Now propaganda reports write glowingly of how the newly found supply of local labour has both solved this labour crisis and helped increase profits for the growers.

But nowhere is there any real explanation of why hundreds of thousands of people, who apparently had no previous interest in picking cotton, should suddenly rush into the fields.

Although the documents claim that pay levels can top 5000 RMB ($763, £570) a month, one report appears to suggest that for 132 pickers organised from one village, the average monthly salary was just 1,670 RMB ($255, £188)) each.

Whatever the salary level, paid labour can still be considered forced labour under the relevant international convention.

Just outside the city of Korla in Xinjiang, as recently as 2015, there used to be an patch of open desert.

It is now home to a giant, prison camp complex, with what independent analysts say are multiple factory buildings visible inside.

It is just one of many such complexes that now dot the landscape and a chilling final reminder of the blurred boundaries between mass incarceration and mass labour in Xinjiang.