Hardoi district in Uttar Pradesh continue to struggle with literacy

Lack of supportive government schemes and access to education has the literacy rates of the villages dropping even further

Hardoi, Uttar Pradesh: Lokmanya Khera, a picturesque rural area in the Hardoi district—about 50 kilometre away from the capital of Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow—has a prevailing problem of access to proper education for a while now. Hardoi district ranks 51st among all the districts of Uttar Pradesh in literacy, with the literacy rate being 64.6 percent which is below the state average of 67.7 percent.

The entire area has very few primary schools with not enough infrastructure to provide adequate educational facilities to all the children of the village. Samrat Ashok Shikshad Sansthan and Bharat Khera are the only two primary schools available within the radius of Lokmanya Khera.

The primary schools provide education up to the fourth standard. “A lot of the teachers have other jobs to attend to too,” said Sikha Maurya, mother of two. “They do not come to the school regularly.”

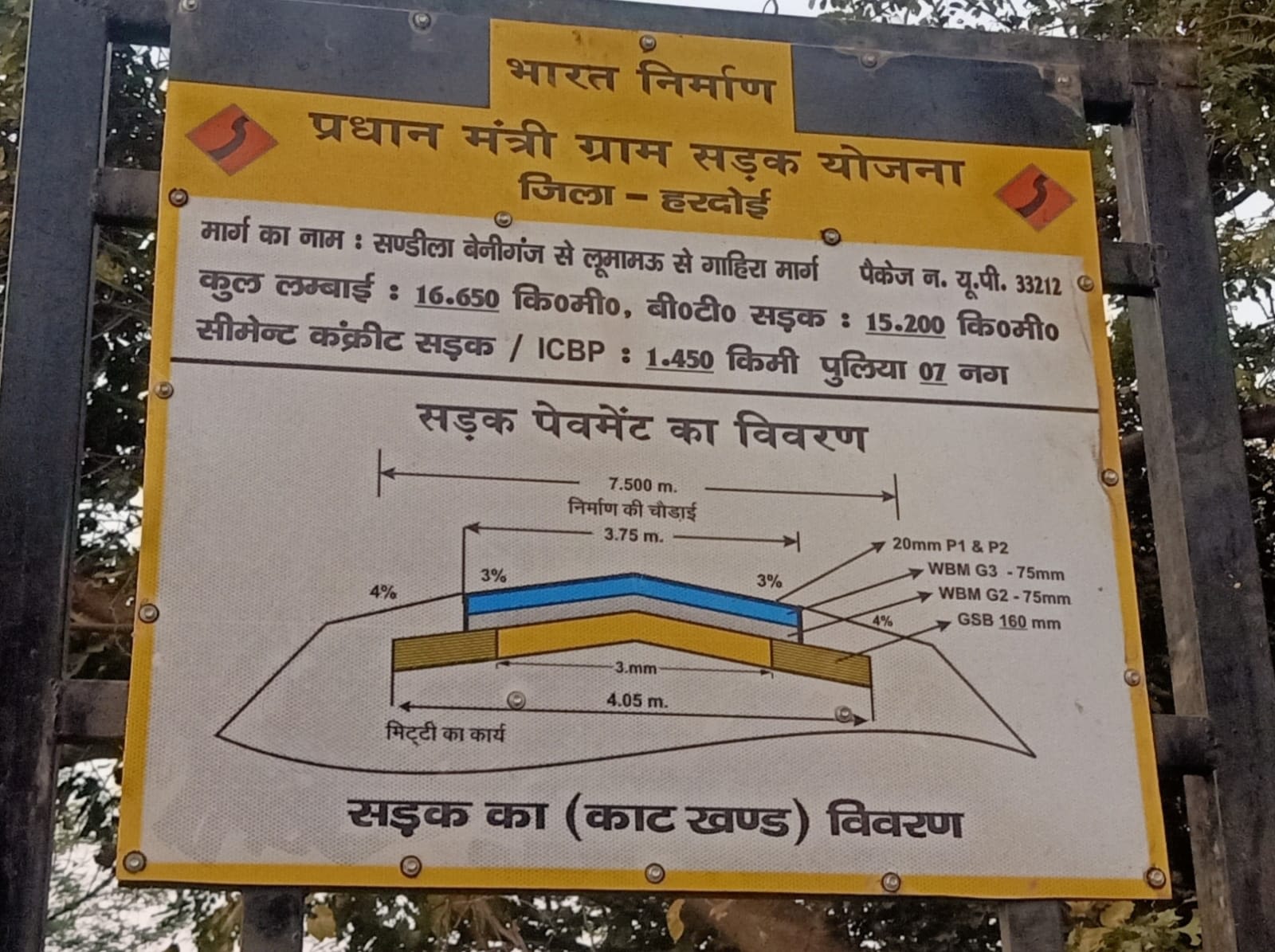

“The students are also not able to attend the school regularly due to lack of connectivity between the villages,” said Anil Kumar Misra, Village Health Secretary. “There are some villages in Lumamu that do not have a primary school, so some student from other village have problem to reach.”

Lumamau is a sub-division in the Sandila block which has 12 villages under it. The villages are mostly occupied by SC (scheduled caste) and OBC (Other Backward Classes) population. Each village has only one primary school while secondary schools are far scarcer

The upper castes of the villages, who are financially better off, often send their children to Sandila where the primary and secondary schools are better equipped. However, most of the students are from much more humble economic backgrounds and cannot afford to go.

Principal of the Neta Subhash Chandra Bose Inter College in the Badhian Khera village of Lumamu said, “The only occupation of the entire village is carpentry and they do not have the resources to send these children far away for better education.”

Despite several attempts of the government, the condition of education in these villages has not improved for the past decade. “Midday meals are irregular and hence not much of an incentive for the students to attend regularly,” said Mohan Singh, a social worker

There are often no regulated system to distinguish kids according to their age and most of the times students are put into a random class at the time of their admission. For instance, a 3 year old kid shares a same class with a 6 year old child. A major number of the students drop out at later levels either due to financial stress, familial issues, or even early marriages among girls.

“The Muslim population of the village do not pay any attention to education,” said Chhetrapal Maurya, the ex-Pradhan of the gram panchayat of Sandila, “Only 10 percent of the Muslims are literate and that too they mostly prefer to attend Madrasas."

The income rates of most of the villages in the area are pretty low and the government schemes have proved inefficient in terms of help. “MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) has been uselessand the people here continue to suffer. Maybe if the system was digital, it would have been more effective,” said Rajesh Kumar Misra, another member of the gram panchayat.

“I am an agricultural labourer and I hardly earn enough to keep the roof above my family’s head,” said Ram Prasad “My son had to drop out of the seventh grade to help me by earning something.”

The secondary schools are far few in number, spread across the area. “After finishing primary school from the Primary Path Shala in Kinauti, a lot of my friends dropped out. Only a handful of us walk about seven kilometers everyday to come to secondary school,” said Shalini Maurya , a student currently studying in Kinauti primary school.

“We cannot afford to send all four of our children to high school. So, we make them study the primary level and then drop out,” said Sikha Maurya.

The literacy levels, tangled up in various social issues related to caste based educational politics, have been regressing and as a result, most of the population has been stuck in a poverty trap for ages.