Encounters with Elephants

After his death, a small-time coffee planter's family is left behind to deal with elephants frequenting their land.

In Hassan district’s Sakleshpur taluk, a region well known for its Robusta coffee plantations, and tea-laden hilly homestays, much larger creatures than urban tourists have been coming through.

Before the crack of dawn on the 1st of September 2020, a priest rose earlier than usual and ventured out of his three-room house to fetch water for his rituals, later in the day.

At 6 AM in Sakleshpur’s Kollahalli, there was little to no visibility. Unknowingly, the priest, Aasthik Bhat, 58, walked right into an elephant, a mere 50 meters from the front of his house. It stood silently, unmoving, along with a calf and another adult.

According to his 71-year-old sister, Girija, who also happened to be awake at the time, the elephant picked him up and threw him a few feet away.

"Bega Banni Elaru!” (“Come fast, everybody!”) She shrieked.

A 53-year-old Kumara, who has been working on their land for the past 45 years, rushed to the spot first, got hit on his abdomen and thrown by the elephant as well.

His wife and another sister, Gayatri, who were still sleeping, rushed outside.

None of them could do much more than just wait. For 20 minutes, the elephant stood motionless next to Bhat’s body, said Girija. He was still breathing by the time Kumara took him to hospital, but he died on the way in the car. The post-mortem reports suggested kidney failure and heart attack due to blunt trauma.

Interestingly, Girija noted that the very same elephant visited the spot where it killed the priest for three consecutive days.

“He was wearing a white panche (dhoti), maybe that’s why the elephant got angry and attacked him…I don’t know if the elephant made any sound that day, but with it being so dark outside in the early morning, he would not have seen it.”

Recently as well, she said, a single male elephant comes by their land at least once a week around 9-11 PM. Their small farm is a few meters off the NH-75, and leads to a densely packed forest.

Who’s responsible?

Aasthik Bhat is survived by his wife, Jayalakshmi and 25-year-old daughter, Kavya who currently lives with her husband.

In her 26 years of marriage, and staying at the farm, she only saw elephants frequenting her home and backyard over the last two years, but she doesn’t know why.

“He (Bhat) was a good man. He had many well-wishers.”

While remembering the incident, she said that the forest department do patrol and announce the presence of elephants in the vicinity. They also shoo them away with fire-crackers and other methods, but not much else has been done.

After receiving immediate monetary compensation from the government, specifically the Forest department, she said she could get her daughter married, but they are still surviving on that sum of money for the last year and three months.

“The elephants also destroyed our coffee plants, areca nut plants, pepper creepers, and the only working well we had.” Currently, their small-scale coffee plantation across five acres is not being maintained and their annual income is approximately Rs. two lakhs.

Speaking of government compensation and attention, Jayalakshmi said, “the politician, Arvind (Limbavali) came down and made promises to set up water connection in the house, and posed for the media.” Yet, no such promise has been fulfilled by the MLA and ex-Minister for Forest so far.

The forest department immediately gives 25% of a one-time total payment of Rs 7.5 lakhs to the family of the deceased due to a wildlife attack on the day of the incident.

Jayalakshmi points out the spot where her husband was killed.

A framed photograph of Aastik Bhat.

A framed photograph of Aastik Bhat.

The family's calf rests in front of the farm's coffee beans set out for drying.

The family's calf rests in front of the farm's coffee beans set out for drying.

“Even now there is just fear… we are constantly living in fear of what could happen.”

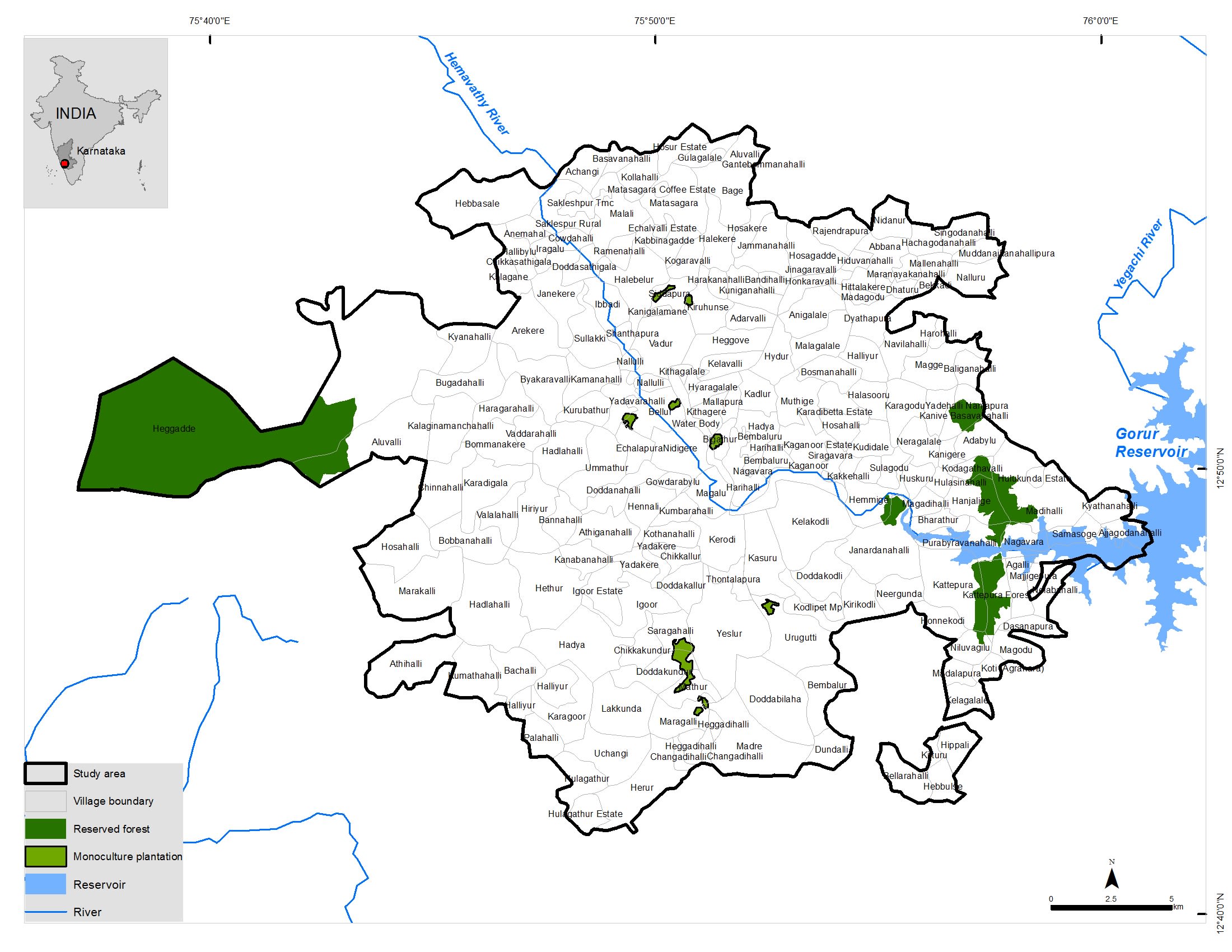

The NCF's study area in the district.

The NCF's study area in the district.

Chasing Elephants

With its lush forests and ample food and water, the elephants of the neighbouring Coorg, Chikmaglur and Western Ghat regions have been crossing over further inland, towards human settlements in Sakleshpur across acres of coffee estates; trampling crops and, often, people to death.

Vinod Krishnan, research co-ordinator at the National Conservation Foundation (NCF) has been tracking these elephants for the past seven years.

Working with the Karnataka Forest Department, he mentioned the radio-collaring of matriarchs of elephant herds over the past few years which allowed them to track herd movement and warn villages and coffee estates of possible elephant danger.

Singular elephants straying from herds, like the ones that visited Aasthik Bhat’s land, cannot be tracked.

Adding that there needs to be a three-way communication between planters, the forest department and locals, he said that the warning systems include a WhatsApp group with planters, where pinned locations of elephant herd movement are shared.

He started a bulk SMS based early warning service in 2017 that now reaches five to seven thousand people, where messages and alerts are sent in Kannada. Audio alerts are also sent for those who can’t read.

Aasthik Bhat’s farm is right off the Bangalore-Mangalore highway, yet elephants seem to be unbothered by traffic. Planters in south-east Sakleshpur put solar-fences, or electric fences around their estates to deter elephants from entering.

“When more and more estates put up solar-fences along their plantations, the elephants can’t always break them, and so they walk along the roads to find an opening to breakthrough,” said Krishnan. This practice has also been driving elephant movement further towards town and human settlements.

“For an elephant, a coffee estate might look like a perfectly natural habitat.”

When asked what attracts elephants towards the Sakleshpur town and coffee plantations, he added that the ample shade, shelter, water, food through seasonal jackfruits and paddy crops provided a ‘daytime refuge’.

Krishnan said that 70% of elephant-caused deaths happen due to people being unaware of them and stumbling into their paths.

“A lot of deaths happened in the past due to lack of toilets and inadequate street lights. Can you really blame the forest department?” he noted that most incidents occur due to people venturing out in the early morning or evenings, where there is little to no visibility, despite the warnings of the forest officials.

Krishnan said that Aasthik Bhat’s death could have been prevented if he had just waited a while longer to venture outside for water.

“Maybe his life could have been saved if he had delayed for daylight.”

“Most fatal encounters happen when people don’t know about elephant presence. This real time-tracking is absolutely vital, especially in Sakleshpur where visibility is so little, coffee estates are dense and there is a lot of people movement.”

Whether people or wildlife be prioritised is a million-dollar question in Sakleshpur, according to Krishnan. Should elephants be removed from human settlements, or should the remaining forests be reserved for free elephant movement?

“Captures are not really helping, as no matter how many elephants we remove, the vacuum will be filled with more from neighbouring areas of Kodagu and the Western ghats.”

Speaking of conservation practises, he said that in largely human-dominated areas, ‘conservation is effective communication’.

“There needs to be a multi-pronged approach. There are socio-political and economic factors that are driving these issues. There is no way we can do anything without leaving out local communities and other stakeholders.”